I am not historically great in selfies…working on it

In Luis H. Francia’s A History of the Philippines the author ends a section titled “The Crescent Against the Cross” with a few sentences that resonated deeply with me. “Not surprisingly, they subsequently viewed each other with mutual suspicion. Despite racial and cultural ties, each to each was the Other: foreign and hostile—an animosity that persists to this day and complicates efforts to negotiate a lasting piece on both sides of the religious and cultural divide.” This concept of other, is of course not restricted to the Philippines. While I won’t use this medium to express personal opinion about what individuals, cultures, religions, races, nationalities, genders, or sexual orientations that my nation’s government labels as other, it is a topic that has recently generated a lot of fervor and discussion due to radical decision-making by the current politically enthroned. I rewrote that paragraph many times, and I think that’s about as tame as it’s going to be.

Islam and Muslim culture is often placed in the cultural spotlight for both the Philippines and the United States. The reason why Francia’s passage rang loud for me was because of a recent opportunity I’ve had through Peace Corps to work on a project hoping to increase awareness of self and of other. The project emphasized empowerment of the self, and worked to bring awareness about the other toward better (safer, happier, more resilient, communicative, tolerant, open, productive, loving) families, communities, and beyond. The program, Padayon Mindanao, simply provided the venue, but it was a group of young Filipinos that forged the path that led from other to brother, sister, kuya, ate, buddy, and friend.

Padayon Mindanao (Padayon meaning continue in Hiligaynon, and Mindanao referencing the southern island in the Philippines characterized by having a significant population of Muslim Filipinos) is a three year peace and capacity building project supported by USAID. The Educate and Engage to Empower Youth Camp that I was fortunate enough to help facilitate invited 24 youth participants from Mindanao and 24 from the host region of Cavite. The project focused on engaging under-served youth from these regions due to increasing numbers of out of school youth and alternative learning system students from conflict-affected areas in Mindanao. Major goals of the camp were to empower participants with self-belief, to increase understanding of civic engagement, and to strengthen links between Filipinos from different regions and cultures.

It wasn’t surprising that I learned a lot while co-facilitating my two sessions; Conflict Management and Problem Solving (oh graduate studies courses will you not leave me alone). In conflict management we talked about the iceberg analogy, the idea that in a conflict there’s a surface level issue or occurrence that we can see (clothing, language, appearance, the physical manifestation of emotion) but the biggest portion of the iceberg is still below the surface. This part of the iceberg remains invisible to others, its home to our cultural and religious beliefs, family backgrounds, personal identity and set of ethics. The eight day camp (and three days Training of Trainers with our Filipino counterparts beforehand) was a process of uncovering some of that iceberg, sharing with each other, and allowing ourselves to exercise cultural understanding.

As a facilitator during these sessions I watched participants unlock deeply rooted stereotypes, work together across religious divides, de-bunk myths held by millions of people within the country, and cry while sharing the personal conflicts and issues in their lives. One session ran thirty minutes over because most of the room was crying during a Muslim participant’s story of religious discrimination in their community. Another explained their excitement to visit Manila for the first time only to be disappointed when individuals moved away from them at the airport upon seeing how they were dressed. Raw emotion out in the open. In a room full of people they had known less than a week. We clapped for each other. Sympathized. We found that many participants faced similar issues in their lives. So we empathized.

Part of my thesis for my natural resource conflict resolution work in graduate school concerned taking the “self” out of conflict situations. I always stressed the importance of neutrality and impartiality as a facilitator/mediator. When co-facilitating these sessions with my counterpart, I found that to be truly impartial to human suffering, anger, and struggle is to move oneself away from the Other. It closes you off from those who are different; it builds a wall. And I use that analogy very intentionally.

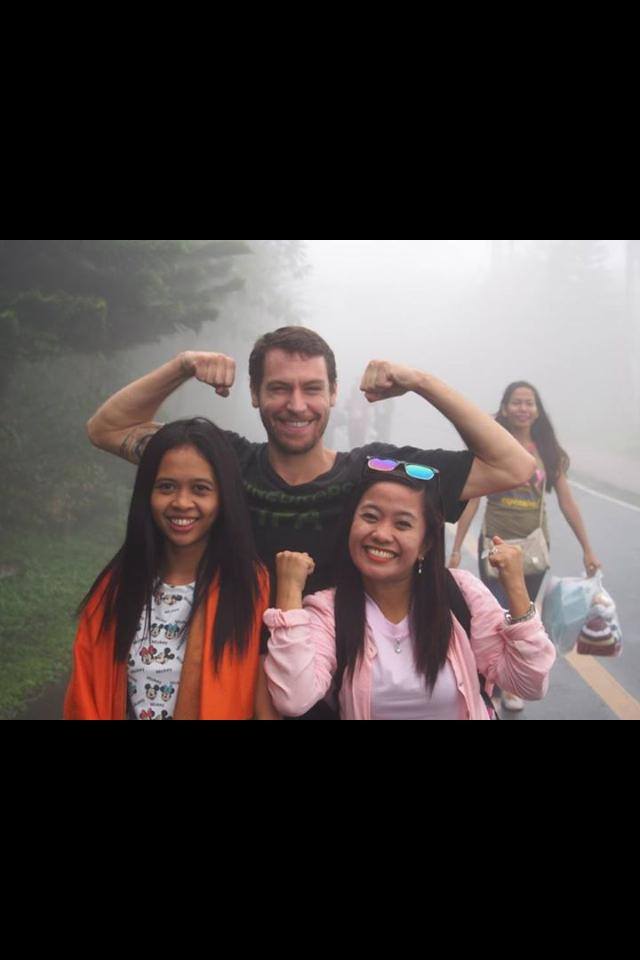

This experience left me with nearly fifty young, brave, smiling, and selfie-loving buddies. It left me greatly inspired by my co-facilitator, a past participant from this program, an ALS graduate, and a current NGO employee in Mindanao. She is unstoppable and the world isn’t ready for her (get ready world).

My counterpart Merry Christ!

My experience with the Padayon Mindanao project also left me marveling at the passage I started this entry with. Hundreds wait… thousands of years of not understanding “foreign and hostile” Others, and I watched a group of young Filipinos engage each other and dis-entangled their collective otherness in a little over a week. They already had the leadership and conflict management skills we focused on, but what we attempted to do, and what I believe we were successful with, was to provide a bit of a lighthouse to guide their ability to become young leaders in a confusing and complicated time. The skill sets and the ability to empower are transferable, and now that they’ve all gone back to their families and communities, the ripple effect continues on.

E2E Camp facilitators and Project Specialist

Counterpart and some of my Tribu for camp (tribe)

Problem Solving session

Camp Day 1

Cultural Presentations

Continue Mindanao, assalam alaikum

d

Maybe the weirdest part was that previously I felt I had come to this rural island in the Philippines and nothing from my pre-PC life would ever find its way to me…nope.

Maybe the weirdest part was that previously I felt I had come to this rural island in the Philippines and nothing from my pre-PC life would ever find its way to me…nope.

Paintbrush (

Paintbrush (